- Tell us a little about yourself and how did you get into photography?

I was born and raised in Beirut. The Civil War ended when I was 12, and as much as I try running away from it, it has largely shaped my view of the world. For a while, I buried it pretty well; I was a math and science nerd in school, so numbers were beautiful and reassuring in how impersonal they were. I went on to study Electrical Engineering in college and enlisted in the army after that. I wanted to specialize in bomb disposals but they weren’t taking any officers during that period, so I left after finishing my service. Thankfully.

Three months into my first job out of the service as a programmer, I had enough money to buy a camera, a 2-Megapixels Canon A60. I wanted one mainly to take family photos. We didn’t have a camera at home until I was in my teens, and the few photos that we had as kids had a lot of sentimental value. I was hoping to replicate the feeling I got from looking at these old photos. It worked to a certain point, and I also experimented with landscapes a little. But then one day I decided to shoot underwater, so I wrapped the cam in a plastic bag and went under. But the seal wasn’t tight and the camera was ruined, so that was the end of it.

- From Lebanon to The United States and back to Lebanon to work on your project. Where were you doing photography when you lived here or was this the first time?

I came to the US in the Fall of 2005 without a camera. I went to grad school at San Francisco State University and I worked there as well. There I found out that people had to file their taxes, a novel concept for me. It turned out that I was owed a tax refund, so with the check I got from the government I bought myself my first DSLR, a Canon Rebel XT.

I was still under some form of culture shock; San Francisco had a lot of homeless people and I hadn’t seen a homeless person in my life growing up in Beirut. So that’s what I started taking pictures of, thinking that I’d be ‘raising awareness’ about the problem, as if I were the first person to think about it. Later on I’d realize how exploitative that was, but I was still hooked on taking photos of strangers and their different expressions. I was also still shooting landscapes as I did in Lebanon, but they were all awful. I had a camera and no knowledge in art or photography. The last art class I had taken was in 3rd grade and it showed. The real learning had to come a few years later after I returned to Lebanon and joined the Beirut Street Photographers. I discovered Giacomelli and Bresson and a whole world opened up.

- Tell us about your project and your experience visiting towns that are called Lebanon; why you decided to do that, any influences or past experiences that enhanced that desire?

I found out about America having so many towns called Lebanon when I was in still in San Francisco. It was during that time when I had just discovered the beauty of road trips, and I thought this would be an interesting trip to do after retirement, visiting all these Lebanons out of curiosity.

I returned to Beirut in 2009 and I worked in finance, first in risk management and then in fiscal laws. Throughout that period, photography moved from being just a hobby into something I couldn’t do without. The idea of quitting my job and going on a road trip across America started brewing in my head, but I kept dismissing it. It’s not easy to throw a career down the drain and forgo a steady income. But then in late 2015 I was in Baghdad for work, and before going I had to submit a ‘proof of life’ form, a document with confidential information to confirm whether I was alive or dead in case I got kidnapped. I didn’t think much of it. Until I got to Iraq and I found a Kevlar vest and a helmet next to my bed in the company offices where we were sequestered. The next day I was in an armored car with two guards and their AK-47s, going to a meeting with government officials. There were barricades everywhere leading to the building because a suicide bomber had tried unsuccessfully to blow himself up there a few days before. That was my main trigger. I said screw it, I can’t live with this crap anymore. I resigned soon after, gave away my rented apartment and most of my belongings and I flew to the US on a tourist visa. I had enough savings to last me a year without a job and I figured I’d start worrying about the future after that year was done.

I rented an RV and started driving. My road trip went on for 5 months. 18,000 miles, 37 States, and over 40 towns called Lebanon visited.

- You visited Lebanon, Pennsylvania (my own state) with population of about 25,000 and Lebanon, Nebraska, population about 70. There are obvious significant differences between the two towns, both on a visual but also on a social and cultural level. Tell us a little about that experience and how that affected your photography.

Lebanon, Nebraska is as rural as it gets. It’s a tiny farming village that has seen better days. When I got there, all the streets were empty. The stores were shuttered. I thought it was a ghost town. I stuck around hoping someone would show up because I was investigating a story about a local college student who went to Beirut in 1955 along with other people from American Lebanons, but instead of returning after two weeks like the others, he went to Jerusalem and was murdered there. The story had CIA links and I really needed to talk to people who might’ve remembered the murder. I was regularly posting about my whereabouts on the project’s Facebook page, and a woman messaged me, seeing I got to her hometown, and connected me with her mother. The story of the murdered man aside, the woman, in her late 70s, told me about the history of the town, one I would hear all throughout the Heartland. With farming machinery getting more efficient in the 1950s, fewer farm hands were needed. Kids left to nearby cities for jobs and stayed there. Populations dwindled, businesses closed, and government cutbacks closed down schools, post offices, and other services. In Lebanon, Nebraska, if you want to go to the closest Supermarket or gas station now, you have to drive to McCook, a city 30 to 40 minutes away. It’s as isolated as can be.

From a photography standpoint, I was a street shooter, taking candid photos of people on crowded streets. But there were no crowds there. So I had to adapt, finding myself increasingly shooting empty rural landscapes because that’s all there was. And with the few people I’d meet, I started engaging with them more and more. I learned how to talk to strangers and, more important, how to listen to them. Very few declined that I take their photos.

Lebanon, Pennsylvania was a different experience altogether. During most of my trip, I was sleeping in my RV at the closest Walmart parking lot, always out of town. But Lebanon, Pennsylvania had its own Walmart and was a noticeably larger city than the others. I arrived there the night before Christmas Eve and the next morning I walked around the stores, taking a few pictures of shoppers and their rush. After months of being surrounded by open spaces, I felt claustrophobic among the crowds. It’s as if I hadn’t lived in packed cities all my life. Thankfully, by late afternoon everybody had gotten home and I was alone in the parking lot. On Christmas day it was empty all the same since the store was closed. These were a rough couple of days too because it was the first time I’d spend Christmas alone.

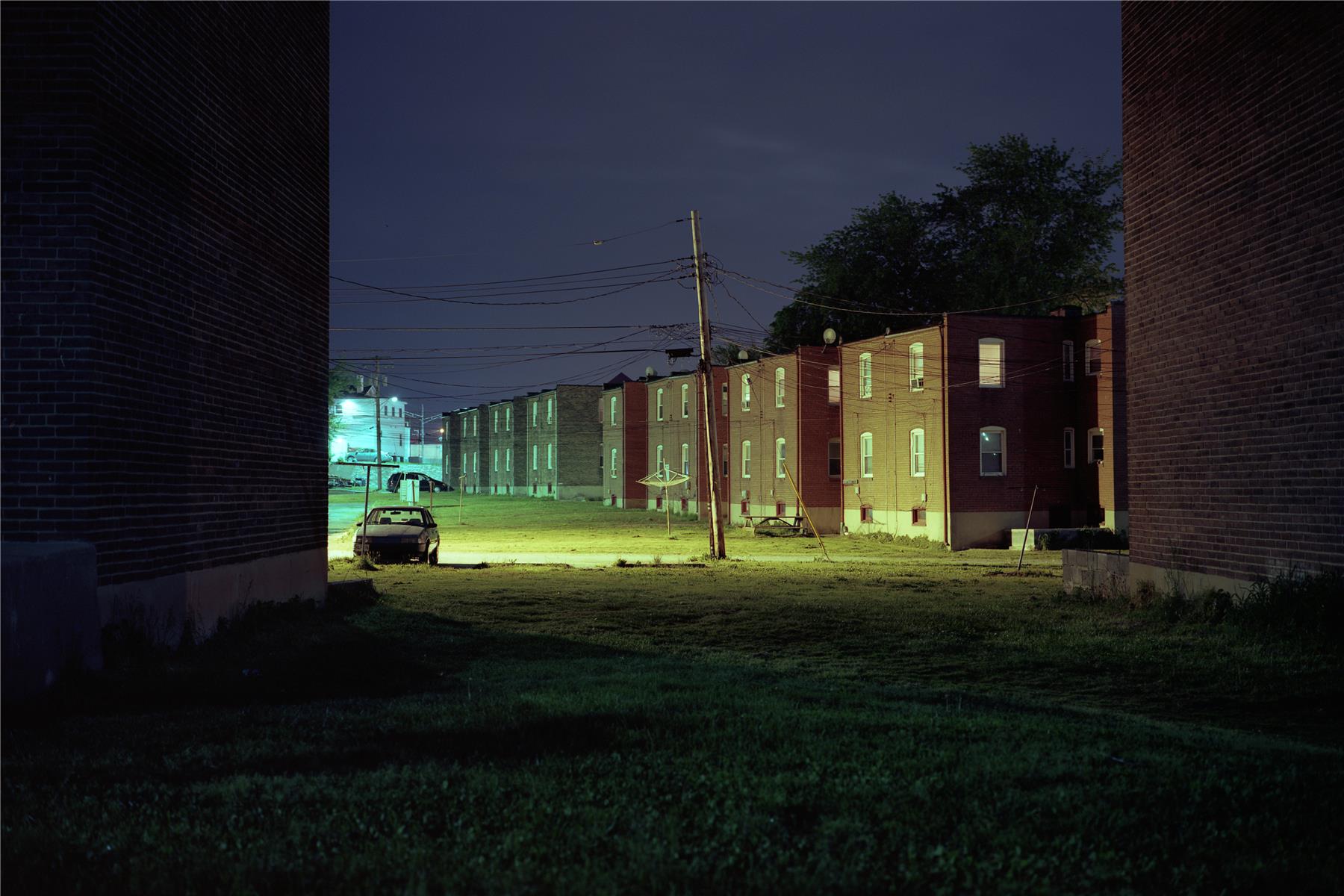

I killed time by driving around, unsuccessfully trying to meet some Amish people – it’s Pennsylvania Dutch country over there – and then eventually just photographing decorated house exteriors. At night I walked the empty streets in the downtown area and the silence was eerie. In rural areas, there aren’t that many houses close together so the quietness is expected. But to walk along city streets lined with buildings and still not hear a peep is unsettling. It was an absence of life where life was expected. The area still hadn’t recovered from the financial crisis of 2008 and it showed.

- Please describe any noteworthy moments from your journeys. Did you visit other towns to photograph or just Lebanon’s?

The Lebanons were a large part of my trip, but I did stop in other cities as well to photograph different events. Folsom Street Fair in San Francisco, Mardi Gras in New Orleans, and the Women’s March and Donald Trump’s inauguration in DC, for example. These stops rounded the out the flavor of the whole trip.

There are far too many noteworthy moments to list, but if I want to sound-bite some: I was invited to an evening of Hassidic Jewish meditation led by Sufi Muslims in a compound built by Christian Shakers in New Lebanon, New York. A Baptist pastor wanted to baptize me in the lake in Lebanon, Oklahoma. I got drunk with Kentuckians in a rundown bar in Lebanon Junction over my own flask of Arak (Lebanese liquor) to prove to them I wasn’t a federal agent. My RV was stolen in Albuquerque, New Mexico by a team of mother-daughter meth-heads. Lastly, I also stopped at the Finlen Hotel in Butte, Montana to recreate Plate #26 from Robert Frank’s The Americans, ‘View from Hotel Window.” (How can a photographer do an American road trip without paying tribute to the master?)

- While you were working on the project the 2016 presidential campaign was in full force. Where you influenced by the frenzy and spectacle in both the social media and new organizations; and from your experience in rural America was your photography influenced and where you surprised by the outcome of the election?

I started my trip from the West Coast, less than a month before the elections. As soon as I moved east past Spokane Valley, Washington, I knew I wasn’t in Clinton territory anymore. Not because of the Trump signs – there were hardly any – but because of the absence of Clinton signs that I had seen everywhere before. The news were filled with one article after the next about the forecasted riots that would ensue if either candidate won, or about the bigotry and danger of the deplorables, as Clinton called Trump supporters, seen through the countless photos of demented people attending Trump rallies. So I was very cautious, believing luck was on my side that I hadn’t met any of the crazies yet. Still, all the polls pointed to a decisive Clinton win, and on the night of the election I didn’t even bother following the results and slept at sundown. But then I woke up after midnight to my phone buzzing; the results had taken an unexpected turn. The minute Trump secured his 270 electoral votes I locked my RV and lowered the shades. I was in the middle of the country (Literally. I was in Lebanon, Kansas) and I got paranoid. I had taken all these media reports at face value and thought someone would soon assault me, either for looking Middle Eastern or for looking Hispanic since even Hispanics in California mistook me for one of them.

The next morning I went to a small diner to have breakfast. I expected the patrons to be celebrating. Nothing of the sort. It was as if they hadn’t just had one of the most contentious elections in history. I tried to pass unnoticed but who was I kidding. I was the only non-white around and had a foreign accent to top. After finishing and as I was leaving the diner, a man sitting at a table with five other men, all in their sixties at least, sees my camera (I was not going to hide the camera) and asks me if I could take a group photo of them. I snapped one quickly because I wanted to get the hell out. Then the man asks me to take a second photo, but this time framing out one of the men because, in his words: “We’re all Republicans and he’s a Democrat.” Then they all burst into laughter, the Democrat included. That was my wake-up moment.

Until then I had believed all these reports about who Trump voters were. But as an American photographer friend later recalled, he went to photograph a few Trump rallies and, even though he was a staunch liberal himself, he was getting annoyed by the fact that journalists and TV anchors were trying to interview only the craziest people they could find. And viewers will only believe – or choose to believe – what they’re being shown, which is a dishonest representation of a substantial part of the population. You either believe they’re all backward racists and xenophobes or you’re one of them. That’s the state of journalism and political discourse in the world today. I wouldn’t even hesitate for a second these days saying that almost everything is fake news. Lying by omission is still lying.

As for photographers, I’ve had this argument with so many of my close friends, who believed that talking to and portraying Trump supporters as human beings was a grave sin. Of the countless photographers I’ve followed covering this topic, there were only two who showed the human side of these supporters: Michelle Groskopf and Stacy Kranitz (Who’s one of my favorite contemporary photographers).

This is where the Lebanese Civil War came at play for me. After it was over, I had to learn, like most people did, how to talk with those whose views are diametrically opposed to mine. To try and find what we have in common instead of dwelling on the differences. It’s surprising how many heavy discussions I’ve had with folks around the U.S. where arguments were defused over a beer (the Budweiser commercial is right; I lived it for 5 straight months.). But a beer isn’t always necessary; it’s important that we check our beliefs and preconceived notions at the door before photographing people. Absent that, empathetic photography is not for you. Maybe caricature at best, or maybe some other profession.

- Your photos blend the descriptive with the emotional, and although you were a passerby, your work has the passion of an insider. The American landscape has been an ongoing theme by many photographers. What is the ingredient that you think separates your work from the rest.

Examining the American landscape and its different subcultures is a job better suited for a foreigner than for a local, especially these days. Having an outsider’s eye means it’s easier to be detached and to see everybody as ‘them’, whereas for many locals there’s always the ‘us’ vs ‘them’, and this translates into a skewed photography, as I mentioned in the previous question.

This being said, yes I don’t mind saying I have the passion of an insider. I’ve been a fan of Americana ever since I started reading my grandfather’s copies of Reader’s Digest as a kid. And I’ve done my homework through years of reading US history and politics, both liberal and conservative, so I have a fair idea about people’s core values. Of course I learned a lot during the trip as well through trial and error. For example, even in the smallest, most rural areas in the country, it’s easier getting access to photograph being a swarthy foreigner than being someone who used to help the IRS catch tax evaders, which was part of my previous job. Afterwards when asked about what I used to do before photography, I would only say engineer, which is still true. And I’d get bonus access points mentioning that both my father and my grandfather were firefighters. Blue-collar people identify better with other blue-collar people.

- Besides sharing images while being an avid user on social media you also shared the story, factual or commentary. Tell us about that decision and how important is the blend of text and images in your work.

When I started the trip, I didn’t think I was going to have deep conversations with the folks I’d meet. I also didn’t think social media was going to turn into this hysteria of political fights, and this isn’t just about Trump or Trump vs. Clinton before it. Even among the Democrats, the Clinton vs. Sanders crowds were getting at each other’s throats.

So when I started meeting all these interesting characters on the road, I knew I had to record it somehow. I tried writing in a journal, but I gave up after two days because I lack the discipline and have little patience for it. I took a lot of voice memos on my phone instead, and I wrote about my encounters on Facebook. I was mostly alone for 5 months and my contact with the world was through that platform. So it both served as a diary and a minuscule counterbalance to all the negativity going around on my feed.

In addition, this made me realize how much I like storytelling in text form. There’s only so much you could say through a photo, and an accompanying text is sometimes needed. At first I thought this makes me less of a photographer, needing to supplement an image with written narratives. But as a reference, I started compiling a list of books that do this very same thing and there was no shortage of them. If Walker Evans and Raymond DePardon and Eugene Richards did it, I think it should be alright for a mortal to do it.

- What does not make a good photograph for you and what does? Are you interested in making photos that stand individually or are part of project?

A good photo is one that raises more questions than it answers through the visual information it presents. Jason Eskenazi puts it in a simpler way: “Don’t be obvious.”

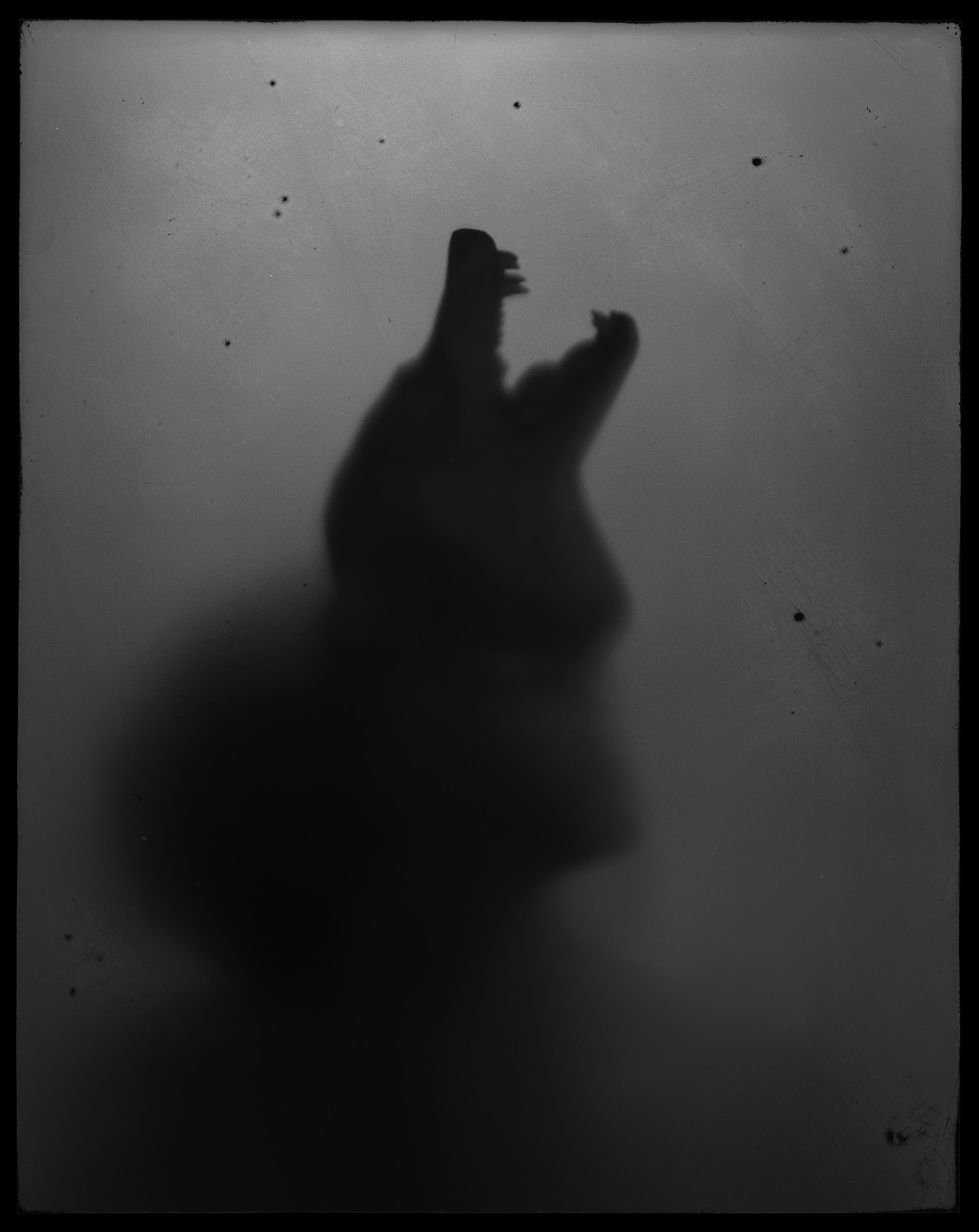

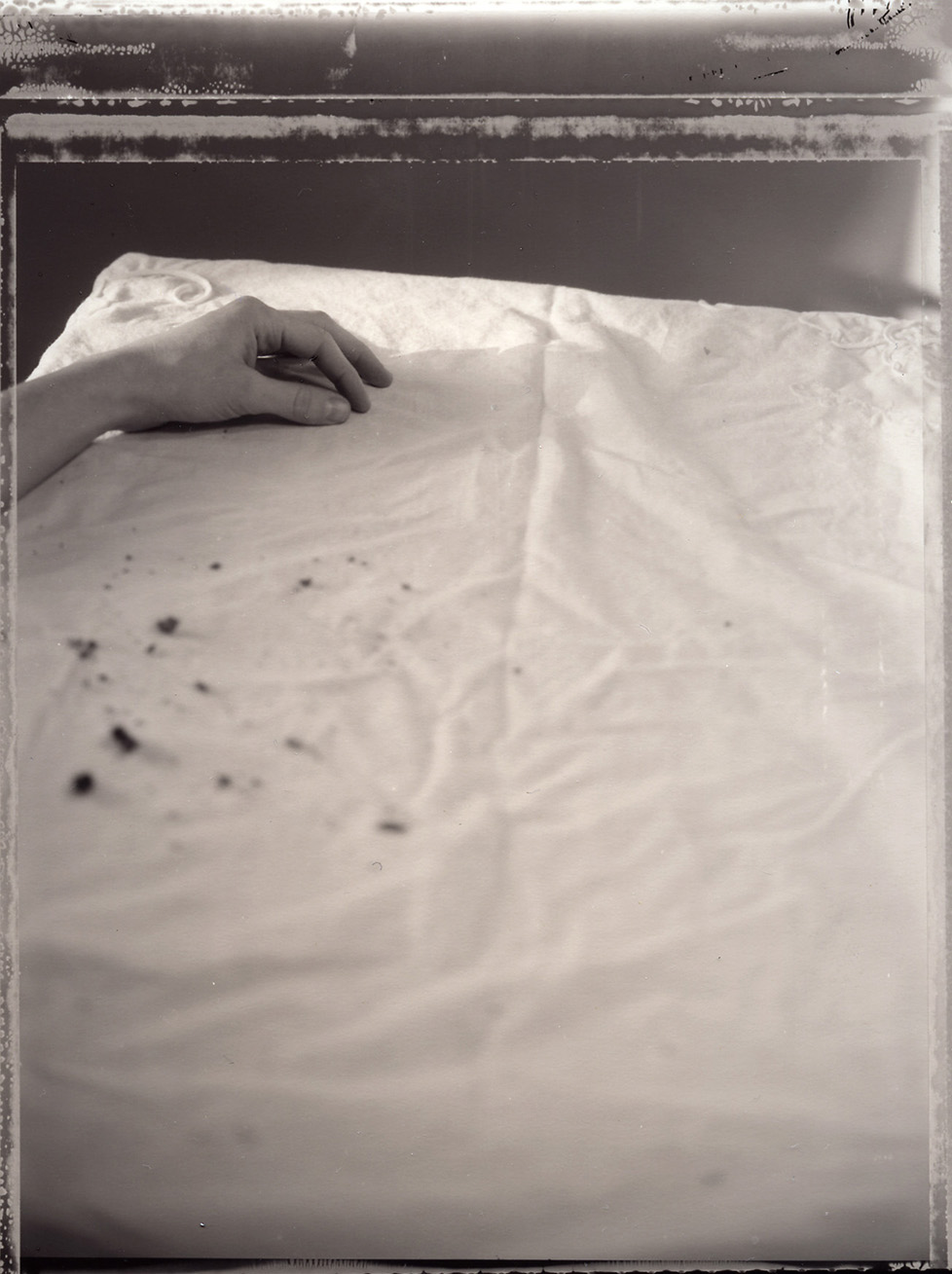

The standalone photo is still the main currency of photojournalism and, to a lesser degree, Street Photography. Everything you’re trying to convey has to be confined within the one photo, and it better be good. But once you work on a project where you’re hoping to imply a narrative through the sequencing – and that’s what I’m interested in continuing to do – a photo has to work within the context of what precedes it and what follows it. So it’s perfectly fine (and sometimes advisable) to include photos that don’t work well individually, but act as a necessary link within the larger project. Even an ‘ordinary’ photo can be needed in a project, if only to release tension from a striking one before it, a détente of some sort to slow down the tempo.

- What are some major differences between photographing in Lebanon and the U.S.?

After visiting large parts of any country, it becomes more difficult to summarize the photography experience in it. Whether it’s in Lebanon or the US or any of the other countries I’ve visited so far, taking pictures in the big cities is relatively uneventful. There will always be some people who don’t want their picture taken, and I respect that. But there is a difference is how people behave on the street. In New York or San Francisco, for example, people in public places behave without much worry about who’s looking at them. You can easily find someone running with an umbrella with a plant under their arm, or someone feeding their dog their own ice cream. In Beirut, there’s an unwritten rule that you need to behave ‘properly’. So you could sense that people aren’t as carefree outside, and this reflects on their facial expression and body language.

When it comes to villages and rural areas, both Lebanon and the US are the same. People are suspicious of an outsider with a camera. Asking for permission and gaining a minimum of trust are needed before you can go on shooting.

- What have you learned from your journey; both as a photographer and a person?

Photographically, this trip has been a crash course in documentary photography. For 5 years I had only been shooting Street, meaning observational candid photography of people in public spaces. Once I hit the rural areas, the streets got empty, as I mentioned earlier. Since I wanted to know who the people who lived there were, I had to get over my anti-social habits and learn how to talk to strangers and listen to them. This was incredibly rewarding because the stories I’ve heard were a treasure trove of life lessons. I’m a sucker for oral history. Listening for example to a hundred-year-old woman in Kansas telling me about her experiences during the Dust Bowl in the 1930s was a gift I’d never have discovered had I not approached her and asked how it was like when she was growing up in town.

What I learned as a person parallels the photography lessons. My interest in Street Photography grew out not wanting to talk to people unless forced to. I was a regular misanthrope. But believing that humankind is garbage and believing people are decent aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. I still think we humans are selfish and destructive, but I also find that there is kindness and decency if you look for it.

I’m not trying to be Mother Theresa or Ghandi here, but why not focus on the good instead of pointlessly festering in all that is bad?

- What are you planning to do with the project and do you have any plans to come back and continue the project?

Right now I’m in the process of going through the photos to edit them down, and compiling the stories of my encounters with all these different people on the road. There’s going to be a book published, but I still haven’t decided about whether to combine photos and texts into one book, or to publish a photo book with an accompanying travelogue diary. I’m aiming for mid-2018 to publish.

Regarding coming back, yes I’m definitely planning to. This whole lifestyle of living on the road is addictive and few experiences could top it for me. The next trip would have a different focus, though. I want to explore the history of Lebanese immigration to the US from the 19th century to the mid-20th century, i.e. before the war. I’d like to see how the original families integrated, how they view their identity, and what they retained from the old country traditions. So it’s time learn about grants and government funding to make this happen.

http://www.fadiboukaram.com/

http://www.lebanonusa.com/