- "Self-taught photographer ... with a little help from my friends". Tell us how you got into photography and how has been the journey so far?

For most of my life I didn’t take pictures beyond the standard snapshots everyone takes. Once I did get into photography, shortly after college, it was a completely solo undertaking. One of the things that appealed to me about it was that I could do it alone. That’s still a big part of it, but friends have played an important role in how things have developed. Both people I know in person and the many I’ve interacted with online have helped me get better and figure out what I want to create. I know that’s the case for a lot of photographers, if not all, but I think it’s important not to take for granted.

- You have a diverse but coherent body of work that circulates around a particular theme. Tell us a little about the concept behind your work.

Thanks! In most cases the work has driven the concept rather than the concept the work. I didn’t start out with an idea for a photography project. Everything started pretty humbly and it’s stayed that way. More recently, I might go out to take some pictures that will fit in with others to make a “whole” but I’m still mostly driven by a less well defined desire to build on what I’ve done, to give myself more material. I get the feeling that a lot of serious photographers might frown on this idea, but I often think of the work I’m making as something closer to a visual diary. Any projects that might be created are drawn from that larger collection of images, rather than started as a project.

I haven’t sought to create an overarching concept for whatever it is I’m building. I’m happy for it to be a bit ambiguous. That might be a copout but I don’t want to risk over-explaining, especially if I have trouble explaining it to myself. However, my work does reflect a lot of how I feel and think and speculating on some of that is interesting, at least for me. Alienation, beauty, decay, the state of humanity, racism, classism, environmental issues, political issues in general, the meaning of life :) ...all are some of the things I think about. There’s also a fantasy element that’s a strong part of it.

I rewatched Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker recently. I like the feel of that kind of science fiction. It doesn’t need to embellish too much to create a new world. It’s a beautiful film made in one of the most traditionally unbeautiful places, an industrial wasteland. It works largely from found elements and clever improvisation, making the most of the material in front of the lens. Jean Luc Godard’s Alphaville, a different kind of movie overall, also works in that way. These are approaches to seeing that I greatly admire. I don’t want to conflate cinema with photography, but closely focusing in on key elements and sequencing them together to make something new is a lot of what photography is about for me.

There’s a lot said about the subjective nature of photography. That’s certainly something I would agree with but I like to go further by not just acknowledging my own subjectivity but completely embracing it. I’m comfortable with the idea of trusting in the narrowness of my own experience. I don’t advocate rejecting or ignoring outside influences, which would be both undesirable and impossible, but it’s also important not to let yourself be overwhelmed or to be overly reverent of what others have done. It’s important to leave room for your own ideas, recognizing that they were not formed in a vacuum.

Right now those ideas include a number of loose projects. One is kind of an overall view of America, something that takes inspiration from work like Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects, pulling together various places I’ve been (Baltimore, Pennsylvania, Florida, California, etc.) into one tighter body of work that says something about how I feel about the here and now. Another project relates to walls and divisions in American society that I’m calling “Division and Gold.” I’m also thinking about a “Baltimore” book of mostly portraits. The last one has actually evolved into a working rough draft.

- You work predominately in Baltimore and Pennsylvania, among other places. What is the relationship to those places and what is the nature of the projects?

Proximity plays as big a part in it as anything. I live right in the middle of Baltimore. I can walk outside and find interesting things or people to photograph without trying too hard. Maryland’s a small state and Pennsylvania isn’t far away. I’m from California originally but moved to rural south central Pennsylvania when I was a teenager. I never really felt at home, but that’s where I spent high school and college. Now I love going back to Pennsylvania, both to photograph but also because I enjoy so many things about the state. It’s a dense environment for someone with my interests. I never feel like I’m coming home, but rather returning with greater appreciation and a sharper eye.

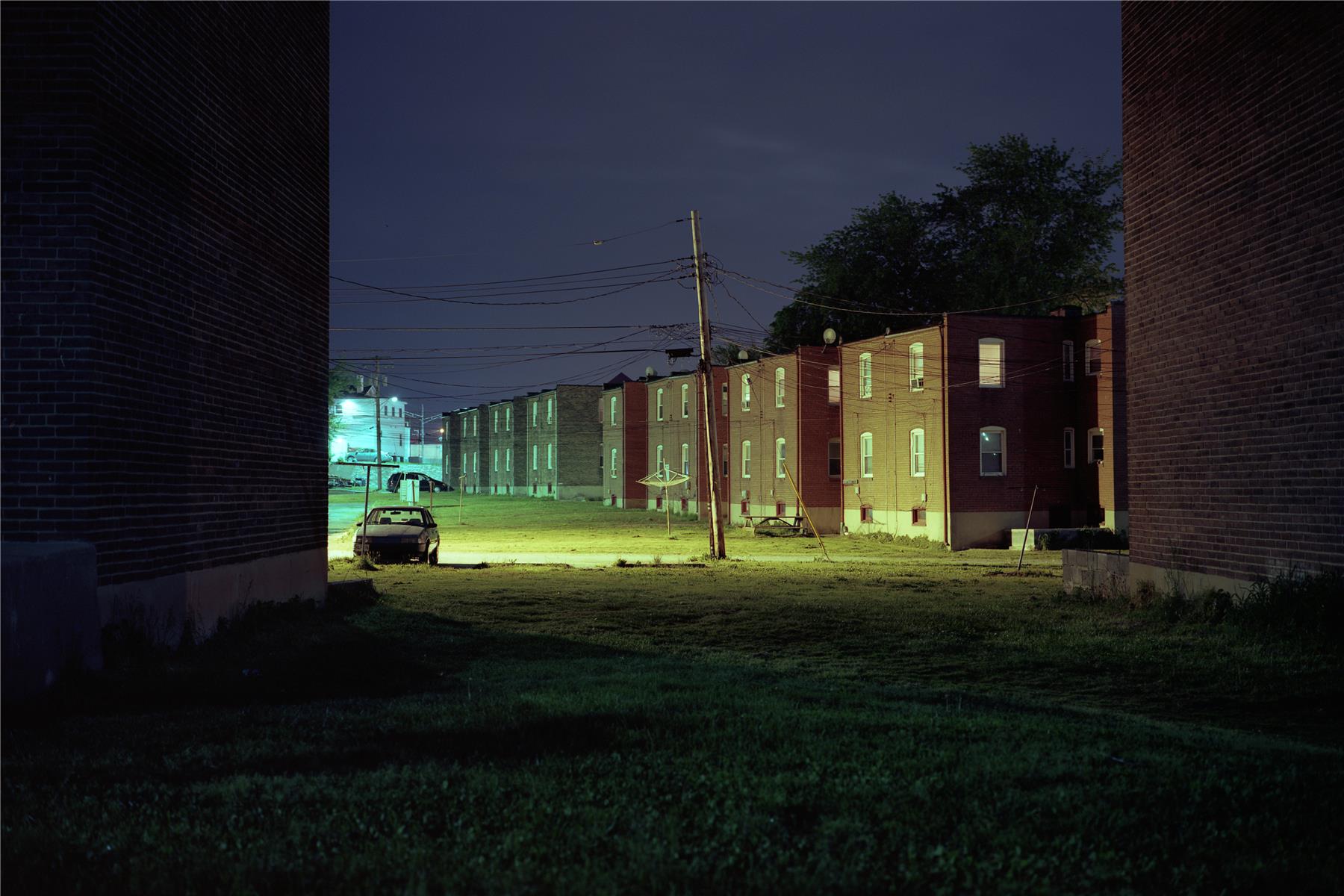

My work in Baltimore is by far the most comprehensive though and my experience here has helped to shape my worldview. I keep wanting to make links between the work I produce here and other places I visit. I mentioned how I can just walk out my door to go to take pictures. Part of what makes that so engaging are the contrasts. If I look left, and on my own block, I can see a relatively well cared for and beautiful old neighborhood, where I can walk to restaurants, libraries, concert venues, etc. To my right are empty lots and decrepit row homes, the result of redlining policy, other forms of racism, the war on the poor, etc. These lines between “good” and “bad” neighborhoods are certainly striking and Baltimore has famously been shown as a city with the worse kinds of “urban” problems, but while I find myself reminded of this daily, I don’t see things differently once I leave town and go to other cities or rural areas in the country. In many cases the divisions are all the more obvious.

Even though I’m interested in lines and divisions, I find myself photographing a lot more in economically challenged areas. That’s not at all uncommon for a lot of photographers. I often question my motivations. I’m not always satisfied with my answers but I think a lot of it has to do with seeking out what is special in those areas. This process really got started for me when I first moved to Baltimore as an Americorps volunteer. Since my work, mostly tutoring children, brought me to the less touristed parts of the city, I was able to actually experience these areas and learn to appreciate them. I had no reason to visit them before, but since that time I’ve always wanted to go back. As a society, we’re used to condemning whole neighborhoods, towns and cities, but when you go to these places, not just read about them but go there, you can find a lot of originality and beauty that isn’t present in the homogenized outlands of suburban America.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the work of Simon Norfolk and his approach to war photography. Long before I made pictures I had a love for classical European painting. I spent a lot of time going to art museums, even skipping school to see the Vermeer exhibit when it came to the National Gallery in the 90’s. There are a lot of different artists I’ve been interested in, but painters like JMW Turner, Claude Lorraine, Hubert Robert, Caspar David Friedrich and Giovanni Panini, with their depictions of real and fanciful ruins, drew me in from a young age. I’m still attracted to those images. Simon Norfolk harkens back to that kind of imagery with his depictions of the toll of war on much of Afghanistan. His photos are beautiful and yet these images, recorded in the best light and reflecting the natural attributes of the land, are records of epic tragedy. Even though the word “war” is too often thrown around in our vocabulary for things that it's not, the waste that has been laid to so many cities and towns, in the United States, is similar, though the process is clearly more subtle. Part of my attraction to the places I photograph in east and west Baltimore, Schuylkill County, or areas around Pittsburgh is the simultaneous beauty that these places possess, in their semi-ruined state, but also how that state represents the tragedy of racism, classism and uncontrolled capitalism. I feel contradictory emotions. The attraction is a kind of trap. I appreciate the beauty and how places in a state of decay can convey a sense of timelessness, but I’m also forced to think of the history that led to these conditions and my own part in that process. These aren’t Roman or Anasazi ruins, they’re part of a present reality, history that’s still in the process of being made.

In contrast to ancient ruins, most of these places aren’t empty. They’re not ghost towns. People live there. There is a deeper beauty reflective in people’s determination to make a home for themselves wherever they are. While it’s harder for me to do, especially when I leave Baltimore, it’s important for the work to also capture the people I see and to collaborate with them in some way, however brief. What I like about portraits is that it’s not just me framing the shot, but a joint endeavor between subject and photographer. Even though I’m editing the photos later, the collaboration allows for an honest outside influence on the work.

- Do you believe there is a significant difference in the impact and result of the work when one is ingrained and familiar with the place he photographs, in relation to a photographer visiting a particular place to make photographs?

It certainly can make a difference. However, living directly in the place you want to make images can sometimes prevent you from seeing things “fresh.” Though I think I’m pretty good at fighting that inclination, I can still sometimes feel a little worn out if I don’t get a chance to find myself somewhere new. I don’t travel all that much, compared to many people I know, but I do it enough that it helps me appreciate Baltimore more when I come back. Also, even though I love Baltimore and have lived here longer than anywhere else, I still feel a sense of distance from it. East coast cities can often take a long time to absorb outsiders. That being said, I don’t know if I want to be “absorbed.” There’s a part of me that needs to have something between me and reality. I take some comfort in how the camera can make me feel close but also feel apart.

A lot depends as well on what you are trying to achieve with your images. Someone like Robert Frank didn’t get to know, in any intimate way, most of the places he traveled in order to create The Americans. That didn’t matter because he was able to convey something more broadly profound. Since making photographs is a visual process, the excitement of seeing something for the first time and responding to it is very powerful. It’s what drives a lot of photographers and certainly me. You can also be someone like Milton Rogovin or Vivian Maier, both of whom travelled, but also did most of their work in their respective cities of Buffalo and Chicago. If you’re embedded in a place you can’t help but tell a very different story than someone who is just passing through.

I value both approaches. I like the idea of being pulled out of my home to literally stretch my horizons, but I also appreciate the opportunity to delve deeper into areas I think I already know.

- A lot of your images are at night and of a particular and mysterious mood, oscillating between the surreal, cinematic and psychological. Is the approach more of an inner exploration of self or a particular and alternative interpretation of a place?

I really appreciate this question because it nicely encapsulates what I’m trying to do, much of the time. My approach is as much about inner exploration as it is about creating an alternative view of a place. I’ve had a lot of interest in magical realism in literature and, without being too forced, I’ve tried something similar with a lot of my photography. As I've already mentioned, I embrace the subjective role of photography and how the images you take, select, and sequence can be arranged to convey a sense or an idea.

I often find myself thinking of certain scenes that I find and how they might fit it in with others. Geography can be a natural way to classify images, but it’s been less important to me in recent years. Much of the time I’m trying to create a new geography out of these various places. I like having the sense of the real and surreal in the same image, but even more importantly, in the thread of images I might put together.

In literature, magical realism doesn’t divorce itself from reality, in many ways it’s all the more entrenched in it. The whole point, or at least what I take from it, is to be able to use the magic to reawaken our sense of the real, to knock us out of the lull we are in when we encounter everyday life and situations. That’s something of what I’d like to do with much of my photography.

- How long have you been working on the Baltimore project and the others that concentrate in your area and are these ongoing? Also, talk about some of the challenges that you encountered and overcome while making the projects.

I’ve been photographing in Baltimore since 2002 and I hope to continue doing so indefinitely. Both my wife and I are pretty entrenched in this city. It feels weird sometimes to think that we might live here for the rest of our lives, but that’s not a negative for me. I love this city. It’s beautiful. It feels like an amazing opportunity to photograph here, or make art of some kind, for decades to come. I think I will have really achieved something if I can do that. It’s easy to get distracted, but my goal is to stay engaged and keep producing work. If I’m flexible enough I think it’s an achievable goal.

- Which photographers, artist, authors and the like, have been your influences and where do you derive inspiration to constantly produce new work?

I mentioned several already. Rather than attempting to be comprehensive I’ll mention ones I’ve been thinking about the most lately. Greg Girard is someone I’ve mentioned to a lot of people. He has a new book coming out soon. I already mentioned Milton Rogovin, but I’ll mention him again because I don’t think enough people know about his amazing life’s work. Maude Schuyler Clay’s portrait work is often on my mind. I’ve also been really into the work of Justine Kurland, and her approach to doing work and having a sense of balance in her life. She has a new book too.

I’ve been inspired a lot by the movies. Early Spielberg movies, Jean Luc Goddard, Terrence Malick, Luis Bunuel, were all big influences long before I started taking pictures. Movies like The Conversation, Parallax View, A Man for All Seasons, Don’t Look Now, Henvy V, Killer of Sheep, are all ones that have really stuck with me.

Music is a big influence as well. My mom introduced me to classical music when I was a kid and that’s still a big part of my life. I like a lot of different music and have many friends with varying tastes and that’s something I appreciate. I don’t know if any of the music influences the work, but it certainly inspires.

- Considering a very dense and competitive marketplace, how do you manage to promote your work and maintain an aesthetic that makes you work distinct?

I don’t think of myself as being in a marketplace, which probably helps. I want people to view my work and it’s been very gratifying that it’s gotten such positive attention over the years. The attention I have gotten has been a motivating factor to keep producing the work though I try not to let it dictate everything I do. The best thing I’ve done to promote my work is to continue doing it and to set personal goals for what I want to achieve. Those goals often don’t have anything to do with traditional ideas of success. I’m honestly just pretty thrilled that I’m able to make work that I can look back on months or years later and be proud of and that other people are excited about too. I know that certain pictures will be very popular and others less so, but It’s important that I create what I want to, regardless of popularity. I like the examples of Morris Engel and Ruth Orkin, photographers and movie makers who did what they had to in order to create their own vision. Whether that vision caught on or was recognized was secondary to the need to create. If what you’re doing comes before all the rest, that’s bound to help or at least it’s nice to think so.

Because of the saturation of images right now, luck has something to do with getting recognition as well. That’s always been a factor, but it’s even more so now. I see a lot of good work that doesn’t get the attention it should. We’re in an unprecedented time when so much great art is being created. The Internet is at the heart of that, of course, and there is certainly plenty of repetition that goes along with this explosion, but I think that there is truly an amazing amount of worthwhile activity to get engaged in. It’s just not possible to keep up with it all, even in the most superficial way. A lot of things follow the standard restrictions of the “art market” which can make things more exclusive than ever. It’s important for artists and art lovers to follow their own instincts as much as possible, to see what’s going on around them, not just what gets featured or anointed.

- What do you consider to be a successful image and what is the importance, if any, of working on a theme rather than making single images that do not relate?

I have long thought more in terms of how a group of images work together rather than in terms of single images. When I’m hanging work or sharing on social media, I like to arrange images together in some way, playing with themes loosely.

I use social media as a way of gauging whether images I make come across the way I want them to. This isn’t always easy but in the absence of formal critiques, I use what I have. It especially helps when I know I’ve engaged, in some way, artists whose work I like and admire. I certainly do plenty of self-editing, but I think the opportunity that social media provides, as part of the editing process, is valuable. It’s not just about showing off. You can use those resources to improve your work.

- What advice would you give to students or someone that is interested in picking up photography?

One of the best responses I’ve seen from artists in terms of advice is the importance of continuing to do work and making sure you accommodate that need even if it sometimes threatens to inconvenience you or others. For me, there really doesn’t seem to be a choice. I must keep making work so what I try to do is arrange my life in such a way as to make that possible. As I’ve achieved a small level of success, it’s also meant that I’ve had to weigh some opportunities with others and make choices about what I pursue. For instance I was asked recently to curate a photography show. I was flattered to be asked but when I gave it more thought I realized I didn’t have the desire or time for that. That being said, sometimes doing something different, something that you weren’t planning on, can have a stimulating effect and steer the work in an interesting direction. It’s not always easy to decide which is the best call to make but again, making sure that you leave time for your work (and to decompress), is important.

- What is your opinion about the current state of American photography in all its manifestations?

I read recently about how there weren’t enough artists documenting Trump’s America. It was an article focusing on the work of Danny Lyon and while it was interesting and I love Danny Lyon’s work, I thought the author’s premise, that there essentially weren’t artists around willing to do work like Lyon, was incorrect. I’m not bringing this up to talk about Trump but just to say that there are a lot of images being taken recording many aspects of our society but you might have to do a little work to find it. It’s not going to just wash over us in a facebook feed or mainstream press. I’m amazed at just how much great work is being done in Baltimore alone. The work is out there. I think that’s probably obvious for any of us who are really interested not just in our own photographic work, but that of others, but I think it’s important to realize that we’re also in our own bubble. We can’t take it for granted that much of this is reaching the mainstream.

The issue has less to do with what’s being created but with what’s being consumed. We live in a time of extraordinary access, because of the Internet, to so many things, but one of the biggest issues is the tendency of so many of us to only consume news, entertainment and conspiracy theories that are tailored to our own specific interests. We have access to all the great books but we’re not reading them, we’re playing games and swiping through things quickly on our devices. It can be hard to find a larger view or contradictory views of all that is going on. Consumer culture has a stronger grip on us than ever and it’s a constant distraction. There are plenty of photographers of all stripes creating compelling images, but they’re not reaching audiences the way that some photographers like Danny Lyon, Gordon Parks or Mary Ellen Mark did. Amazing photo essays are being created all the time, but they’re seen by hundreds or thousands, not millions. I’m not sure what individual photographers can do about that issue since it’s just a small part of a larger problem. The good news though is that whether audiences are interested or ready for it, the work is there and it’s beautiful. I find myself constantly inspired by what I see others creating. I feel very lucky to be alive in such a culturally rich environment where so much in the arts is easily accessible.

http://patrickjoust.com/